Princess Sophie of Prussia (1870-1932) married Crown Prince Constantine of Greece (1868-1923) amid great pomp and splendour in Athens in 1889. Her wedding dress of imitation Venetian lace and silver brocade, which I discussed in my previous post, and her trousseau were worthy of a future Queen of the Hellenes, if the accounts in the German and English newspapers of the day are reliable.

At the time, well-bred brides took everything they could conceivably require to their new home in their trousseau, which included dresses, hats, coats, mantles, shawls, linen (a broad term that covered underwear, nightgowns, handkerchiefs, bed linen and table linen), jewellery and silverware. Princess Sophie’s trousseau was no exception, but it probably eclipsed that of most brides in terms of quantity, filling about 200 trunks.1 Lace had pride of place, encompassing various lace-making techniques; it was supplemented by a set of Honiton lace, a gift from Queen Victoria, Sophie’s grandmother,2 who actively patronized the British lace industry and encouraged the use of Honiton lace at weddings within her own family. Contemporary newspapers remain tantalizingly silent about the cost of this vast trousseau, with the exception of the Standard, which, however, gives only the value of the linen and two Indian shawls (yet another wedding present from Queen Victoria): 25,000 marks and 12,000 marks, respectively.3 Most of the trousseau was supplied by Berlin and Frankfurt firms, and reports in German newspapers and the Queen, The Lady’s Newspaper, a London magazine, even identify the purveyors of Sophie’s lingerie. However, the names of fashion houses that provided her with evening and court dresses, daywear and coats are omitted, probably to prevent the dissemination of copies of the designs, thus sparing Sophie the chagrin that would have inevitably resulted from the knowledge that other women were wearing outfits that resembled her own.

Unfortunately, the reporters of the time also refrain from mentioning the quantity of the various items that Sophie would take with her to Greece. Articles speak glowingly about the sheer amplitude of her lingerie and its craftsmanship, for example, but say nothing about the number of undervests,4 camisoles,5 nightgowns, stockings and so forth that she had ordered. On the other hand, the Standard tells of five toques and “eleven arrangements of flowers and feathers” to be worn as hair ornaments.6 By this account, it would seem that Sophie did not have many hats, but it is likely that only these lavishly decorated toques, which, in the German and Greek popular imagination, would have been appropriately ostentatious headgear for a future queen, were selected for display in the public exhibition of her trousseau.

The trousseau itself was not preserved for posterity and verifiable images of the garments do not exist, making a study of its individual elements impossible (especially in the absence of an inventory detailing names of vendors, amounts paid, number of items ordered, etc.). Nonetheless, primary sources in the form of the afore-mentioned periodicals offer an overview of what such a collection might have looked like. My discussion of the trousseau, which is divided into three posts, is also informed by 1889 issues of Der Bazar, a prominent women’s fashion magazine published in Berlin that Sophie herself might have consulted while assembling her bridal wardrobe. This post (Part I) deals with the bride’s lingerie and the clothes she would wear in the intimacy of her marital home, as well as the fine and valuable laces she would use to decorate her gowns, while her day dresses, outerwear, hats and hair ornaments form the focus of Part II. Finally, Part III takes evening dresses, court clothing and jewellery as its subject.

Lace

The highlight of Princess Sophie’s lace, and the focus of much praise in the newspapers, was a flounce of white point de Venise, made by the Berlin lace manufacturer B. Wechselmann.7 It was thirty-five centimetres in height and had a pattern of intertwining myrtles and roses with appliquéd flowers; narrow laces displaying the same design served as an accompaniment.8 There was also a black flounce of Chantilly lace with floral designs that exceeded one metre in height and had narrow pieces of matching lace, as well as coordinating barbes and fans.9 Chantilly lace obtained its name from a town in north-east France that produced black continuous bobbin laces in the second half of the eighteenth century; the lace owed its dainty appearance to the use of half stitch, as opposed to whole stitch, for creating naturalistic floral motifs.10

Such laces could be conveniently tacked onto an evening gown, removed afterwards and stored for future use; thus, the wearer could utilize the same pieces of lace throughout the course of her life to change the look of different garments. While Sophie could have used either of the above-mentioned large flounces to embellish a skirt, the narrow laces from the same set could have appeared as trimming on the bodice’s neckline and sleeve cuffs. The long Chantilly lace flounce, which would probably have reached from the wearer’s waist to her feet, was versatile enough to be styled in two different ways: that is, asymmetrically draped over the skirt front, so that it would be visible through the opening in the overskirt, like the swathe of lace in figure 1.2, or hanging straight in folds, as in figure 1.3.

Lingerie and home-wear

The firms of F. V. Grünfeld in Silesia and Jules Bister in Berlin, as well as Edmonds, Orr and Co. in London, supplied the lingerie portion of Princess Sophie’s trousseau.11 All of her linen, including the table linen, was embroidered with her monogram, an “S” surmounted by a crown.12

Sophie’s lingerie was undeniably elegant and luxurious, thanks to the use of Valenciennes lace for embellishing her underwear, in the form of chemises, undervests (some of which were also threaded with ribbon) and camisoles, and her handkerchiefs of French lawn.13 Although originally a Flemish town, Valenciennes capitulated to Louis XIV (1638-1715) in 1678, and its speciality, a continuous bobbin lace “with a broad but light and ethereal design,… with a minute line of holes pricked evenly around each motif, made of 1,200-count thread and produced therefore with a cosmic slowness,” became a French lace.14 The production of Valenciennes lace eventually moved to other centres in France, as well as Belgium, which fashioned it as a sturdy lace for the undergarments of Queen Victoria, Empress Eugénie and other customers.15

Sophie must have been one of the few women who could pack her trousseau trunks with underwear trimmed with costly Valenciennes lace. Der Bazar, while giving a round-up of lingerie trends in an August 1889 issue, emphasizes the sheer range of expensive Valenciennes-ornamented chemises and predicts their popularity amongst customers:

Hemden… mit Valenciennespitze ausgestattet und mit farbigem Band durchzogen, ganz allerliebst aus… und dürften manche Liebhaberin finden, wenn unsere Damen hören, dass von dieser Sorte durchaus keine Dutzendzahl bedingt ist. Man rechnet sie, eben weil die Sache etwas ungewöhnlich ist, zu den über den Etat greifenden Luxusartikeln.

Shifts… decorated with Valenciennes lace and with coloured ribbon running through them, look absolutely lovely… and are sure to find many a fan when our ladies hear that there are certainly not just a dozen of this type. Precisely because the item is somewhat exceptional, it is counted as an over-budget luxury article.16

An article that appeared in the Neues Tagblatt after the wedding, while gushing over Sophie’s sophisticated taste in underwear and sleepwear, outlines the ways these items combined Valenciennes lace with a variety of other textiles and different types of embroidery:

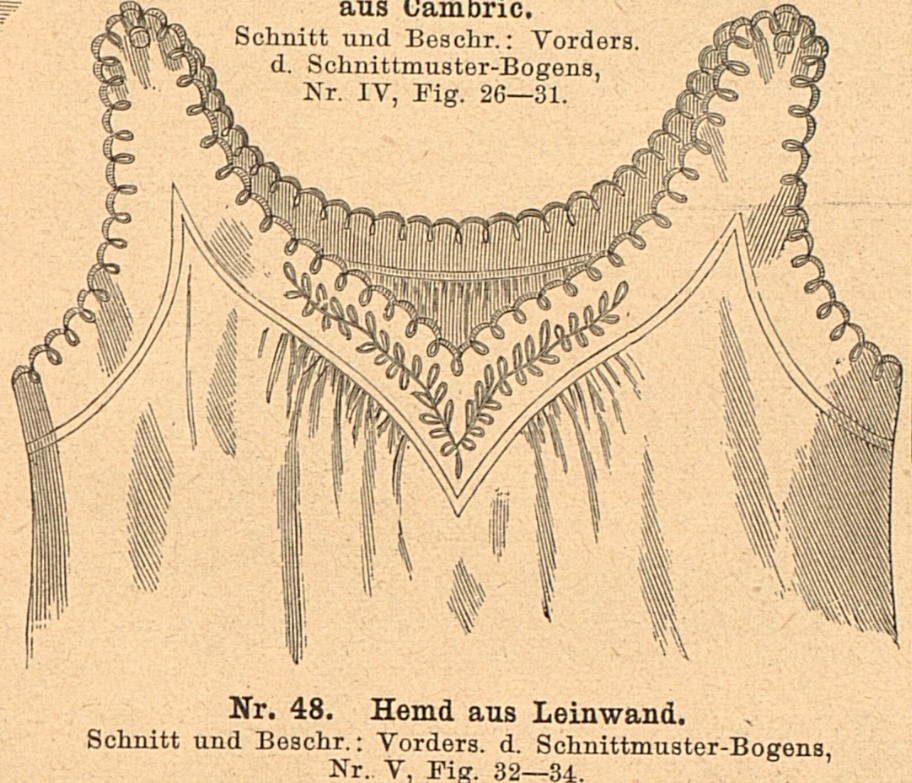

Was die Wäsche betrifft, so hat die Prinzessin selbst überall die Wahl getroffen und Stoffe, Spitzen, Festons, Stickereien, Durchbruchmuster nach eigener Angabe konfektionieren lassen. Die Leibwäsche ist aus feinstem Grasleinen, teilweise auch aus echter Brussa-seide gefertigt. Man sieht da nicht die überladene Pracht, die sich oft bei Ausstattungen reicher bürgerlicher geltend macht; alles einfach, stilvoll, kunstgerecht. Tag- und Nachthemden sind in Form von Devants Bräute sehr geschmackvoll mit Valenciennes und Handstickereien garniert; vielfach ist Handarbeit statt der Maschinen-stepperei mit besonderer Feinheit und Accuratesse ver-wendet. Die seidenen Hemden fallen vorteilhaft durch ihre Einfachheit auf. Der Rumpf ist ganz glatt, vorn nur eine Passe mit farbiger Festonstickerei, oben gleicher Bund.

As far as the lingerie is concerned, the princess herself made the choice throughout and had fabrics, lace, festoon borders, embroidery and openwork patterns made according to her own specifications. The underwear is made from the finest grass linen, in some cases also from real Brussa silk. One does not see the excessive splendour that often appears in the outfits of rich bourgeois brides; everything simple, stylish, artistic. The fronts of chemises and nightgowns are very tastefully decorated with Valenciennes and hand embroidery; in many cases, needlework is used instead of machine stitching with particular delicacy and accuracy. The silk shifts stand out thanks to their simplicity. The body is completely plain, only a yoke with coloured festoon embroidery at the front, a similar band at the top.17

As the preceding description indicates, a skillful, though sparing, use of coloured embroidery in Sophie’s linen provided visual interest to undergarments and accessories that were predominantly white, in keeping with the fashion of the time.

The use of coloured embellishment on underwear was atypical, but Der Bazar strongly encourages it:

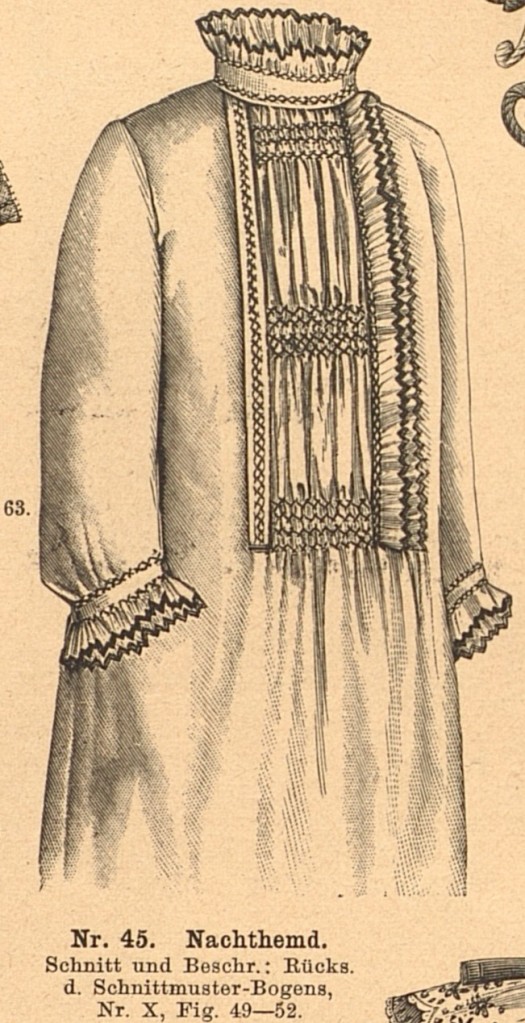

Zum Sticken der Leibwäsche wählt man, wie auch zum Zeichnen des übrigen Wäschebestandes, gern weißes Garn, wenn auch etwas farbiger Zierrat an der Wäsche durchaus nicht ausgeschlossen ist. So z. B. sehen Nachthemden mit einer Garnitur aus farbigen Languettenstreifen und farbigen Fischgrätenstichen, wie solches Abb. Nr. 45 zeigt, ganz allerliebst aus;

For embroidering the underwear, as for the design of other linens, white thread is often chosen, although some coloured decoration on the lingerie is not out of the question. For example, nightgowns look very lovely with a trimming of coloured bands of languettes and coloured herringbone stitches, as shown in illustration Nr. 45 [figure 1.8];18

Languettes, which had a serrated or scalloped edge, were widely used in the lingerie industry—those found on flannel, crepe and worsted-flannel petticoats were embroidered with white or coloured silk—but also featured on garments themselves, such as white promenade skirts.19 In a possible nod to Der Bazar’s recommendation, Princess Sophie included white silk nightgowns with trimmings of coloured languettes, the creation of the firm of Jules Bister,20 in her trousseau.

Her lingerie also incorporated coloured fabrics as decoration; moreover, the nightgowns, consisting of assorted textiles, demonstrated a range of sewing and decoration techniques, designs and styles. As the Standard informs its readers: “Those of the night-gowns which are not of silk are of the finest chamboie, and trimmed partly with lace-jabots, partly with diagonal embroidered insertions, the effect of which is enhanced by coloured lawn under them. There are some also with little crush-folds and broad, turned-down collars.”21

To the already-existing diversity of fabrics—German linen,22 grass linen, silks, chamboie—Edmonds, Orr and Co., a supplier to the British Royal family, contributed items made of Lisle thread, such as camisoles, some of which were also in silk, and stockings.23 These latter were in addition to those made of spun silk, silk and wool; the stockings matched Sophie’s dresses, while others were in black and white and were plain or featured openwork and embroidery.24

Spencer bodices, which, unlike the Princess’s daintily trimmed camisoles, were designed to keep the wearer warm,25 were also included in her trousseau for her to wear when she went riding.26

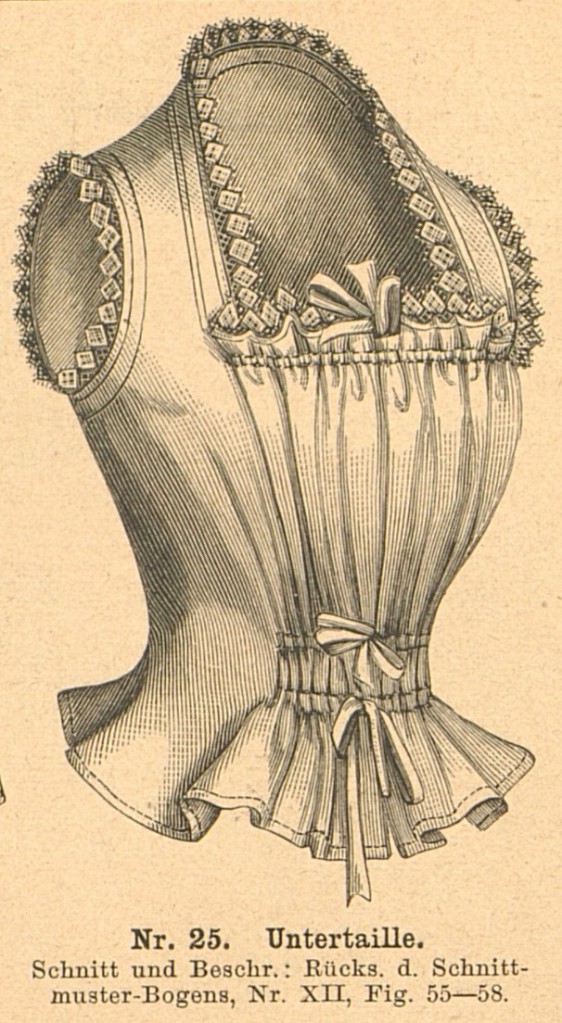

Fashion houses presented Sophie with various options in response to her need for comfortable, informal clothing that she could wear in the privacy of her home. In addition to lingerie, Jules Bister made morning dresses of white wool, with white satin embellishment, for her to don after bathing.27 Embroidery and trimmings of white cambric adorned morning jackets;28 and a pink matinée, or jacket, from the atelier of Gerion and Co., Berlin, was decorated all round with Valenciennes lace.29

From the same firm came a cream-coloured Robe intérieure with a sash-like ribbon, whose long ends dangled in front, based on a model designed especially for Sophie; Alençon insertions and lace embellished the garment’s wide Greek sleeves.30 The use of this outfit, or dressing-gown, would have been restricted to the bedroom;31 as figure 1.11 indicates, there was a vogue for dressing-gowns with sweeping Greek sleeves in 1889. Alençon, which emerged from a town of the same name in Normandy during the early 1700s, was a needlepoint lace made with buttonhole stitches, whose cordonnet (a raised cord outlining the design), unlike that of other laces, had horsehair for its foundation.32

Coming up next: Part II.

Notes

1. “Foreign News of the Week. The Royal Wedding,” Birmingham Weekly Post, November 2, 1889.

2. “The Greek Royal Wedding. The German Emperor’s Reception,” Standard (London), October 28, 1889. Pat Earnshaw, A Dictionary of Lace (Princes Risborough: Shire Publications, 1982), Internet Archive, describes Honiton lace, which took its name from a town in East Devon that had been known for lace production since the seventeenth century, as a “non-continuous bobbin lace of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries” with “typical fillings such as diamond, toad in the hole, blossom, and swing and a pin; and typical design units called bullock’s hearts, turkey tails, Devon rose, pear border, beetle-head sprigs and orange blossom” (80). Bobbin lace (or pillow lace) was the outcome of a “modified weaving process which takes its name from the way it is made – with bobbins, usually of bone or wood, on a pillow or cushion… [in] non-continuous [bobbin lace]… the closed sprigs or motifs are made as one operation and the linking of them by brides or by mesh as another” (18-19).

3. “Greek Royal Wedding.” In 1889, 25,000 marks would have equated to around 202,500 euros or $219,186 in 2023 money, whereas 12,000 marks would have been the equivalent of approximately 97,200 euros or $105,209 in 2023. For the marks to euros conversion rate, see “Purchasing Power Equivalents of Historical Amounts in German Currencies,” Deutsche Bundesbank, last updated January 2024, https://www.bundesbank.de/resource/blob/622372/d64726452d1eb2f62ce667f6784f89bb/mL/kaufkraftaequivalente-historischer-betraege-in-deutschen-waehrungen-data.pdf. “Foreign News” reports that Sophie’s linen cost more than £1,000, while “The Royal Wedding at Athens. A Great Function,” Derby Mercury, October 30, 1889, reveals that the two Indian shawls gifted by Queen Victoria cost £600. These amounts would equate to about $169,062 and $101,437, respectively, in 2023 figures, according to Eric W. Nye, Pounds Sterling to Dollars: Historical Conversion of Currency, accessed March 20, 2024, https://www.uwyo.edu/numimage/currency.htm.

4. The undervest, an item in use since the c. 1840s and worn by both men and women, was an “under-garment, on the hygienic principle of “wool next the skin,”… usually of merino, thigh-length and sleeved;… from 1875 ladies adopted coloured vests of washable silk and gussets shaped for the breasts were then introduced.” C. Willett Cunnington, Phillis Cunnington, and Charles Beard, A Dictionary of English Costume (London: Adam & Charles Black, 1976), 225, Internet Archive.

5. A camisole was: “A short-sleeved or sleeveless under-bodice of white long-cloth, worn over the stays to protect the tight-fitting dress.” Ibid, 35.

6. “Greek Royal Wedding.”

7. “Aus der Reichshauptstadt,” Hallesches Tageblatt (Halle), October 12, 1889, https://www.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/newspaper/item/OEGVST23C22XNLZYEPN2EB2YHXZPABSY?issuepage=3. See Faiza Mahmud, “Princess Sophie of Prussia’s Wedding Ensemble,” Lost and Found blog, January 31, 2024, https://dressingroyalty.wordpress.com/2024/01/31/princess-sophie-of-prussias-wedding-ensemble/, for my discussion of point de Venise.

8. “Greek Royal Wedding;” “Aus der Reichshauptstadt.”

9. “Greek Royal Wedding.” The Oxford English Dictionary, while indicating that the term “barbe” first came into use in around 1374, defines it as, “Part of a woman’s head-dress, still sometimes worn by nuns, consisting of a piece of white plaited linen, passed over or under the chin, and reaching midway to the waist.” In other words, a barbe could be a headscarf or kerchief. On the other hand, Earnshaw, Dictionary of Lace, points out that barbes were synonymous with lappets, a pair of lace streamers “attached to the back of the head and obligatory for court wear from c 1660 to well into the nineteenth century” (97). “Aus der Reichshauptstadt” mentions “Barben und Tücher,” which translates as barbes and shawls, but makes no reference to fans.

10. Earnshaw, Dictionary of Lace, 31, 77. Continuous bobbin laces, the opposite of the “non-continuous” variety, were “worked straight across between footing and heading, the ground and the denser parts in one” (35). In bobbin laces, whole stitch and half stitch were “two main stitches used to make the solid parts of the design… Whole stitch is more closely worked and gives the appearance of woven linen. Half stitch is more open, looking like a grill of intersecting stars” (77).

11. Ida Barber, “Feuilleton. Die Ausstattung der Prinzessin Sophie von Preußen,” Neues Tagblatt (Stuttgart), November 1, 1889, https://www.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/newspaper/item/X5UUUH5EZWMYWNEFHW63WHF56U26QXRC?issuepage=2;” “A Royal Trousseau,” Queen, The Lady’s Newspaper, May 18, 1889, 688.

12. “Greek Royal Wedding;” Barber, “Feuilleton.”

13. Barber, “Feuilleton;” “Royal Trousseau,” 688; “Greek Royal Wedding.”

14. Earnshaw, Dictionary of Lace, 177.

15. Ibid.

16. “Über Leib- und Hauswäsche,” Der Bazar. Illustrirte Damen-Zeitung, August 26, 1889, cover page, https://digital.ub.uni-duesseldorf.de/ihd/periodical/pageview/2996244.

17. Barber, “Feuilleton.” The Oxford English Dictionary defines openwork as, “Metalwork, needlework, etc., having decorative or ornamental openings,” and has the following entry for grass linen: “A fine, light linen-like cloth originally made in China and plain woven from ramie or other strong plant fibres.” Brussa silk came from Bursa (Turkey), which, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica, was also known as Brusa or Prusa and enjoyed an international reputation for its silk production.

18. “Über Leib- und Hauswäsche,” cover page. Cunnington, Cunnington and Beard, Dictionary of English Costume, claim that the use of the languette was prevalent during c. 1818-22, identifying it as, “A flat, tongue-shaped, applied trimming, a common decoration for skirts and pelisses” (124).

19. “Über Leib- und Hauswäsche,” cover page.

20. “Aus der Reichshauptstadt.”

21. “Greek Royal Wedding.” It is unclear what sort of textile “chamboie” might refer to.

22. Ibid.

23. “Royal Trousseau,” 688. Harry P. Curtis, Glossary of Textile Terms (Manchester: Marsden, 1921), Google Play, describes Lisle thread as, “Yarns made from the finest of long staple cotton” (164). These are “passed over a gas flame to burn off any fiber ends;” Lisle is, moreover, “the smoothest, most lustrous cotton knit possible (closest to fine linen knit); it is used for… stockings for those… who… want something sturdier than silk!” notes Mary Humphries, Fabric Glossary (Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall, 1996), Internet Archive, 131.

24. “Royal Trousseau,” 688.

25. The spencer bodice made for Princess Sophie may have been the same as the late-nineteenth century “flannel or knitted sleeveless spencer… worn under the jacket for extra warmth by the elderly or infirm” mentioned in Cunnington, Cunnington and Beard, Dictionary of English Costume, 202.

26. “Royal Trousseau,” 688.

27. “Aus der Reichshauptstadt.”

28. “Greek Royal Wedding.”

29. “Aus der Reichshauptstadt.” According to the Oxford English Dictionary, a matinée was, “A woman’s lingerie jacket or wrap for morning wear.” Cunnington, Cunnington and Beard, Dictionary of English Costume explain that it was, “A hooded pardessus made of jacconet or muslin and worn outdoors over a morning dress” (134); a pardessus was any outdoor garment of half or 3/4 length, with sleeves and shaped into the waist” (156).

30. “Aus der Reichshauptstadt.” Cunnington, Cunnington and Beard, Dictionary of English Costume, refer to the Greek sleeve as a “Grecian sleeve,” describing it as, “An undersleeve slit open at the side and closed with buttons” (98).

31. Cunnington, Cunnington and Beard, Dictionary of English Costume, 69.

32. Earnshaw, Dictionary of Lace, 3-4; Emily Leigh Lowes, Chats on Old Lace and Needlework (London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1908), 41, 73, 77, https://archive.org/details/cu31924052083924/page/n115/mode/2up?view=theater.

Bibliography

Barber, Ida. “Feuilleton. Die Ausstattung der Prinzessin Sophie von Preußen.” Neues Tagblatt (Stuttgart), November 1, 1889. https://www.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/newspaper/item/X5UUUH5EZWMYWNEFHW63WHF56U26QXRC?issuepage=2.

Der Bazar. Illustrirte Damen-Zeitung. “Über Leib- und Hauswäsche.” August 26, 1889. https://digital.ub.uni-duesseldorf.de/ihd/periodical/pageview/2996244.

Cunnington, C. Willett, Phillis Cunnington, and Charles Beard. A Dictionary of English Costume. London: Adam & Charles Black, 1976. Internet Archive.

Curtis, Harry P. Glossary of Textile Terms. Manchester: Marsden, 1921. Google Play.

Earnshaw, Pat. A Dictionary of Lace. Princes Risborough: Shire Publications, 1982. Internet Archive.

Hallesches Tageblatt. “Aus der Reichshauptstadt.” October 12, 1889. https://www.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/newspaper/item/OEGVST23C22XNLZYEPN2EB2YHXZPABSY?issuepage=3.

Humphries, Mary. Fabric Glossary. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall, 1996. Internet Archive.

Lowes, Emily Leigh. Chats on Old Lace and Needlework. London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1908. https://archive.org/details/cu31924052083924/page/n115/mode/2up?view=theater.

Queen, The Lady’s Newspaper. “A Royal Trousseau.” May 18, 1889.

Standard (London). “The Greek Royal Wedding. The German Emperor’s Reception.” October 28, 1889.