Elizabeth I, Queen of England and Ireland (1533-1603), daughter of King Henry VIII and his second wife, Queen Anne Boleyn. Declared illegitimate when parents’ marriage was annulled in 1536; mother was executed days later. Ascended the throne in 1558, after the deaths of her childless half-siblings, King Edward VI and Queen Mary I. Ruled for over 44 years, relying on the counsel of parliament and advisers. Highlights of her reign include the establishment of the Church of England (1559), defeat of the Spanish Armada (1588), discovery and colonization of North American territory (1583 onwards) and founding of the East India Company (1600). Remained unmarried, leaving the throne to James VI of Scotland.

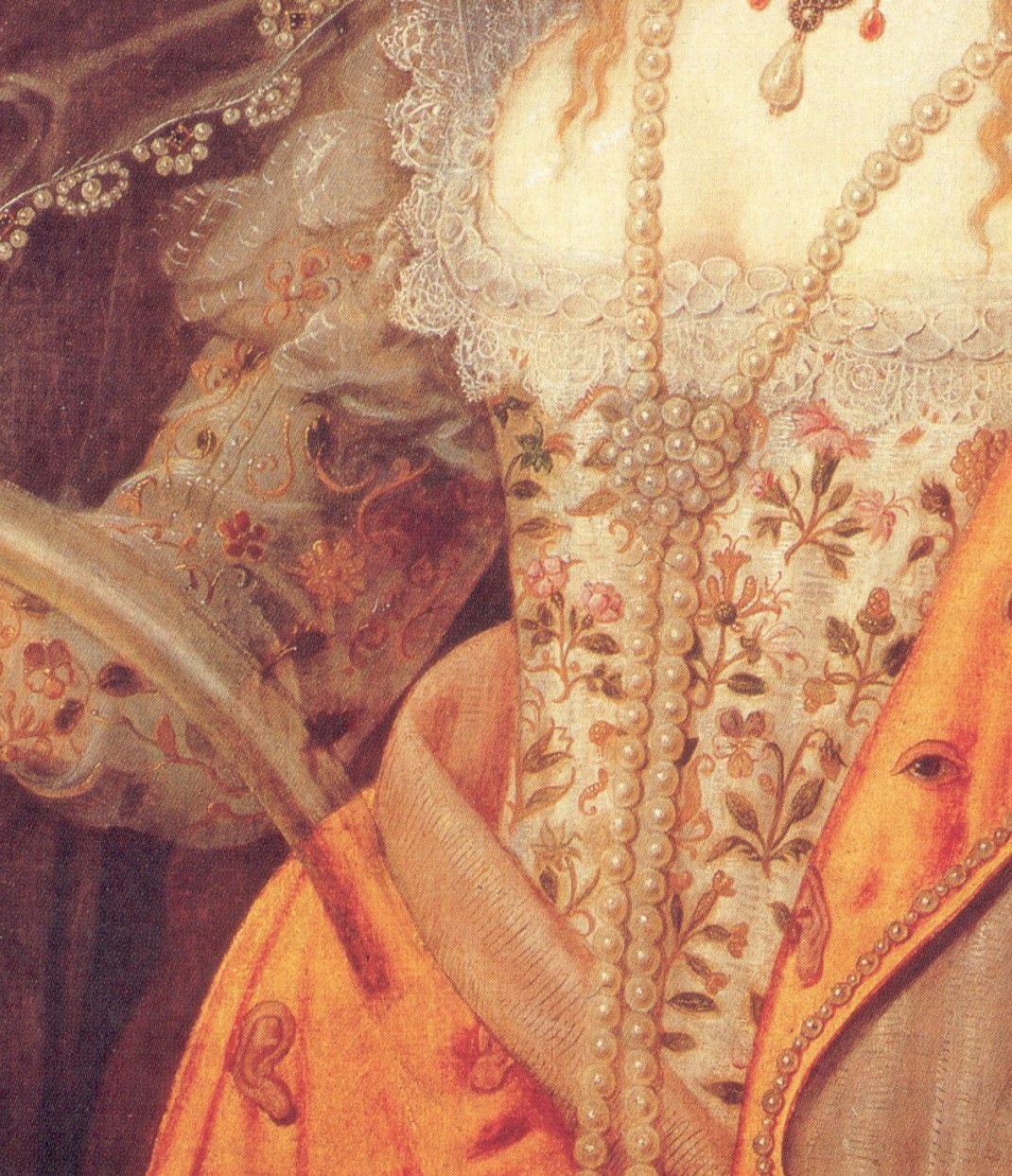

Figure 1.1. Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger (Flemish), Queen Elizabeth I (The “Ditchley” Portrait), c. 1592, oil on canvas, 241.3 x 152.4 cm (95 x 60 in), National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG 2561, source: The Johnston Collection.

When Elizabeth I died in 1603, her wardrobe consisted of 1,900 items of sumptuous dress. There is no evidence that any of Elizabeth’s clothing has survived, as it was standard practice for Tudor monarchs to gift their lavish garments to those in their service, who used the valuable fabric to create other items. Besides falling prey to such thrifty means of repurposing and recycling, Elizabeth’s attire, along with the rest of the royal dress collection, was probably auctioned off in 1649—when Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658) decided to clear out the royal stores after seizing power—or destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666.¹ In recent times, however, two possible survivors from her storied wardrobe have emerged: the Bacton Altar Cloth and the Devereux Bodice, both of which are masterpieces of English embroidery.

1590s

The Bacton Altar Cloth

A large T-shaped piece of textile measuring 6.5 by 3 feet that once covered the altar in St. Faith’s Church in Bacton, Herefordshire, the Bacton Altar Cloth is believed to have originated from a skirt worn by Queen Elizabeth I. Before Eleri Lynn, a curator at Historic Royal Palaces in London, discovered the piece of fabric at St. Faith’s in 2016, area residents had believed for centuries that Blanche Parry (1508-90), Elizabeth I’s Chief Gentlewoman of the Bedchamber and a Bacton native, had embroidered the material herself and presented it to the church. In 1909, however, Reverend Charles Brothers (1862-1953), who believed that the textile had once been worn by Queen Elizabeth, ordered that the altar cloth be placed in a glass frame and hung on a wall in the church, preserved for posterity.²

The material itself is silver chamblet silk, or cloth-of-silver, which is composed of real silver metal threads woven into the cloth itself. The silk of the fabric is of Italian origin. Chemical testing carried out on dyes from the silk embroidery thread have revealed that the red of the Tudor rose is Mexican cochineal, while other dyes come from India. A skilled craftsman directly embroidered floral and vegetal motifs onto the incredibly expensive fabric, probably in the 1590s; this was a method that did not allow for any mistake.³

Such high quality work would only have come from the hands of a male professional, employed at a workshop that was probably located in a large urban centre like London,⁴ and although such workshops also had women embroiderers, membership in the Worshipful Company of Broderers, chartered in 1561, was restricted to men.⁵ This guild was responsible for maintaining the highest standards, and one can assume therefore that only the most talented and experienced embroiderer from its ranks would have been allowed to work on the Queen’s garments.

In contrast, the animal motifs, such as a bear or a deer (see figure 1.3), have been executed some years later by an amateur hand.⁶ It is possible that the Queen’s own ladies-in-waiting created this second layer of embroidery, in order to alter the look of her outfit since their mistress could not purchase a new dress for every occasion. (It is important to remember that such a dress would have cost as much as a good-sized house in the Elizabethan era.)⁷ The lady embroiderers consulted Nicolaes de Bruyn’s Animalium Quadrapedum of 1594, as can be seen from the afore-mentioned bear, which is a direct copy from this illustrated text. Unlike the master embroiderers, however, they embroidered “slips,” that is, individual motifs on small frames or hoops, which they later cut out and appliquéd onto the textile. Such a method of embroidery offered many advantages and flexibilities. If the embroiderer made a mistake, she could discard the slip and start over on a new one. Slips could be removed from dresses, as fashion dictated, or transferred to other items, allowing both the garment and the embroidery to be used over and over again, without damaging an outfit’s precious base fabric.⁸

The professional embroiderer would instead have used a large frame that would have allowed him to work directly on the silver chamblet; ink markings on the Bacton Altar Cloth indicate that he first drew the pattern on it with a pen or a brush. Knowing that there was no room for error, the craftsman nonetheless had great confidence in his ability. Once the fabric was thus embroidered, it could not be un-picked and recycled—a clear sign of the wealth of the owner,⁹ who presumably could afford many such garments. These observations, coupled with the fact that Elizabeth I had enforced sumptuary laws that reserved cloth-of-silver for the highest levels of the British aristocracy and members of the royal family, point to the Queen herself as a potential owner of the textile.10

Although records show that Blanche Parry, the putative donor of the Bacton Altar Cloth, received many gifts of clothing from Elizabeth, it is unlikely that she could have given the cloth to St. Faith’s Church as she died much before the ornately embroidered textile was made and fashioned into a skirt for the Queen. Eleri Lynn has theorized that as Parry had been Elizabeth’s oldest and most loyal and trusted companion, it was the Queen herself or her ladies-in-waiting who sent this magnificent textile to St. Faith’s after Parry’s death, in celebration of her memory.11

While there is no proof that the Bacton Altar Cloth is in fact derived from a dress in Elizabeth I’s wardrobe, there is no denying that it bears remarkable similarity to the textile of the bodice and sleeves in the so-called Rainbow Portrait of the Queen (figure 1.4), attributed to Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger (1561/62-1636).12 Gheeraerts probably took inspiration from contemporary texts while painting the botanical designs on Elizabeth’s gown, and one can easily imagine that the fabric of the skirt, concealed from view by an orange mantle embellished with motifs of eyes and ears,13 would have resembled the altar cloth before it received additional embroidery depicting fauna.

1600s

The Devereux Bodice

The collection of the Kyoto Costume Institute (KCI) in Japan boasts an embroidered bodice from around 1600 that may have belonged to Elizabeth I, effectively debunking Historic Royal Palaces’s claim that the Bacton Altar Cloth is the only known extant example from her wardrobe.14 Lettice Knollys (1543-1634), the mother of Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex (1566-1601), previously a favourite of the Queen who would later be executed for treason, reputedly presented her the bodice, known as the Devereux Bodice (figure 1.5), in hopes of securing a pardon for her son. The gift also included a skirt, which is now missing.15

The base fabric of the bodice is plain-weave linen or canvas.16 Its entire surface, except for the back, is covered with silver thread and all manner of embroidered plant, insect, reptile and avian life.17 Scrolling vine patterns, an embroidery fashion that emerged in the Elizabethan era, gaining popularity in the Jacobean era that followed, are picked out here in chain-stitched gold thread and frame motifs of a rose, forget-me-not, tulip, iris or carnation.18 The embroidery has a three-dimensional quality—the curling petals and leaves seem to be growing out of the surface of the bodice—thanks to the use of the detached needle lace method, which came into use in the late sixteenth century.19

The embroiderer has used polychrome silk threads to produce subtle gradations of colour so that leaves and petals do not look flat. Such differences in tonal value also make the peapods look ripe to bursting: the bulging peas are embroidered in light green thread that stands out from the dark green of the surrounding pods (figure 1.6).

The embroidery also incorporates different types of metal thread, both in gold and silver. Metal strip wrapped around a silk thread has been chain-stitched to create scrolling vines. Additionally, small coils of metal lacking a silk core, known as purl, have been used to create details like the stamens of flowers and also to hold round-shaped spangles in place. Such fine wire (metal purl), also shaped like a coil, serves as the edges of petals, leaves and other botanical elements; metal thread used in this manner enabled the embroiderer to attach petals and leaves, fashioned in needle lace, to the motifs on the bodice so that they project from the surface. The reflective qualities of metal purl, when used in conjunction with intertwining multi-coloured silks, allowed the embroiderer to mimic the gleaming surfaces, complex variegated patterns and spiralling contours of snail-shells.20

Looking at portraits from the same era, one can see similarities between the Devereux Bodice and the clothing of sitters in terms of embroidery motifs and techniques. Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger’s Portrait of an Unknown Woman (figure 1.7) has its subject, once thought to be Elizabeth herself, attired in Persian clothing,21 but its surface decoration is distinctly English. Like the Devereux Bodice, it features a stylized pattern of scrolling vines; these encircle typically English flowers like roses and honeysuckles. In between the coiling stems are small birds that are either flying or perching.22 The bright colours of these floral and animal motifs indicate that the colours of the Devereux Bodice’s silk embroidery have faded over time, possibly as a result of exposure to light.

Another painting by Gheeraerts, titled Barbara Gamage with Six Children (figure 1.8), shows the adult sitter, whose married name was Barbara Sidney, Countess of Leicester (1563-1621), wearing a heavily embroidered bodice whose foundation fabric is unidentifiable. The embroidery on her sleeves has a three-dimensional quality, like that of the Devereux Bodice. Her costume provides guidance as to how Elizabeth I might have worn the Devereux Bodice: with a starched ruff, lace cuffs and an open-front gown having hanging, false sleeves that would have concealed the unembellished back of the bodice from view but revealed its richly embroidered surfaces. The long point of the bodice would have jutted outward over the Queen’s farthingale, per the fashions of the day, but the bodice certainly does not have the long, narrow silhouette that she favoured (see figure 1.1).

Unfortunately, the KCI is silent on the question of who might have embroidered the Devereux Bodice. Since the foundation fabric, unlike the Bacton Altar Cloth, is linen, not cloth-of-silver or a material of immense value, one cannot say with certainty that the embroidery is the work of a professional employed at a workshop, rather than that of an enthusiastic and talented home-based lady embroiderer. Women at all social levels were schooled in needlework; ladies from wealthier backgrounds who could afford pattern books, which became widely available in the late sixteenth century, were able to further develop their decorative embroidery skills.23 Workshops, on the other hand, were likely to have draftsmen who produced original motifs or designs.24 One would like to see further research on the identity or even just the gender of the bodice’s embroiderer(s), sources of inspiration for the motifs, techniques used and length of time required for completing such elaborate work. There are, additionally, many unanswered questions regarding the bodice’s provenance over the more than four centuries of its existence, as the KCI does not offer any clues as to how Wacoal Corp., the donor of the bodice, was able to acquire it.

Notes

1. Meilan Solly, “See Scrap of Cloth Believed to Be From Elizabeth I’s Only Surviving Dress,” Smithsonian Magazine, August 15, 2019, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/scrap-cloth-representing-elizabeth-is-only-surviving-dress-set-go-view-180972919/; Victoria Howard, “The Bacton Altar Cloth – Elizabeth I’s Only Surviving Dress – Now at Hampton Court Palace,” The Crown Chronicles, October 11, 2019, https://thecrownchronicles.co.uk/history/historical-news/the-bacton-altar-cloth-elizabeth-is-only-surviving-dress-now-at-hampton-court-palace/.

2. Solly, “See Scrap of Cloth;” “The Lost Dress of Elizabeth I,” Historic Royal Palaces, accessed February 16, 2022, https://www.hrp.org.uk/hampton-court-palace/whats-on/the-lost-dress-of-elizabeth-i/.

3. Natalie Walker, “Report on the Bacton Altar Cloth,” The Medieval Dress and Textile Society, Issue 86 (July 2018): 7-8. https://www.medats.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/2018_Jul-MedatsNewsletter.pdf.

4. “Introduction to English Embroidery,” Victoria and Albert Museum, accessed February 21, 2022, http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/i/english-embroidery-introduction/.

5. Melinda Watt, “English Embroidery of the Late Tudor and Stuart Eras,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, May 2010, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/broi/hd_broi.htm.

6. Walker, “Report,” 7.

7. Howard, “Bacton Altar Cloth.”

8. Walker, “Report,” 7-8.

9. Ibid.

10. “Lost Dress;” Howard, “Bacton Altar Cloth.”

11. “Lost Dress.”

12. Walker, “Report,” 6,8.

13. Howard, “Bacton Altar Cloth.” Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury (1563-1612), commissioned the Rainbow Portrait; the eyes and ears on Elizabeth’s mantle reflect his role as her spymaster.

14. “Lost Dress.”

15. “Collections |Collections -1700s|KCI Digital,” Kyoto Costume Institute Digital Archives, accessed February 21, 2022, https://www.kci.or.jp/en/archives/digital_archives/1700s/KCI_296.

16. Ibid.; Cristina Balloffet Carr, “The Materials and Techniques of English Embroidery of the Late Tudor and Stuart Eras,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, June 2010, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/mtee/hd_mtee.htm.

17. “Collections.”

18. Ibid.; “Jacobean Embroidery,” Wikipedia, last modified February 2, 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jacobean_embroidery.

19. “Collections;” Carr, “Materials and Techniques.”

20. Definitions of terms and techniques relating to metal embroidery, as well as descriptions of its visual effects, in this paragraph have been taken or are derived from Carr, “Materials and Techniques.”

21. Frances A. Yates, Astraea: The Imperial Theme in the Sixteenth Century (London: Routledge, 1975), 220-21, Internet Archive. The author argues that the source for the sitter’s exotic costume might be J.J. Boissard’s Habitus variarum orbis gentium (1581), which includes an illustration depicting a “Virgo Persica” (Latin for “Persian Virgin”), and connects Gheeraerts’s painting to the Elizabethan predilection for masques. Bernadette Andrea, while conceding that the sitter may not be Queen Elizabeth I, considers the portrait to be an outcome of English attempts to initiate trade, mostly in cloth, with Russia and Persia, as well as the influence wielded by Aura Soltana, a Tartar slave girl who entered Elizabeth’s service and became a trendsetter at her court. See Andrea, “Elizabeth I and Persian Exchanges,” in The Foreign Relations of Elizabeth I, ed. Charles Beem (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2011), 182-86, Internet Archive.

22. “Introduction.”

23. Watt, “English Embroidery.”

24. “Introduction.”

Bibliography

Andrea, Bernadette. “Elizabeth I and Persian Exchanges.” In The Foreign Relations of Elizabeth I, edited by Charles Beem, 169-99. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2011. Internet Archive.

Carr, Cristina Balloffet. “The Materials and Techniques of English Embroidery of the Late Tudor and Stuart Eras.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, June 2010. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/mtee/hd_mtee.htm.

Historic Royal Palaces. “The Lost Dress of Elizabeth I.” Accessed February 16, 2022. https://www.hrp.org.uk/hampton-court-palace/whats-on/the-lost-dress-of-elizabeth-i/.

Howard, Victoria. “The Bacton Altar Cloth – Elizabeth I’s Only Surviving Dress – Now at Hampton Court Palace.” The Crown Chronicles, October 11, 2019. https://thecrownchronicles.co.uk/history/historical-news/the-bacton-altar-cloth-elizabeth-is-only-surviving-dress-now-at-hampton-court-palace/.

Kyoto Costume Institute Digital Archives. “Collections |Collections -1700s|KCI Digital.” Accessed February 21, 2022. https://www.kci.or.jp/en/archives/digital_archives/1700s/KCI_296.

Solly, Meilan. “See Scrap of Cloth Believed to Be From Elizabeth I’s Only Surviving Dress.” Smithsonian Magazine, August 15, 2019. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/scrap-cloth-representing-elizabeth-is-only-surviving-dress-set-go-view-180972919/.

Victoria and Albert Museum. “Introduction to English Embroidery.” Accessed February 21, 2022. http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/i/english-embroidery-introduction/.

Walker, Natalie. “Report on the Bacton Altar Cloth.” The Medieval Dress and Textile Society, Issue 86 (July 2018): 6-8. https://www.medats.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/2018_Jul-MedatsNewsletter.pdf.

Watt, Melinda. “English Embroidery of the Late Tudor and Stuart Eras.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, May 2010. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/broi/hd_broi.htm.

Wikipedia. “Jacobean Embroidery.” Last modified February 2, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jacobean_embroidery.

Yates, Frances A. Astraea: The Imperial Theme in the Sixteenth Century, London: Routledge, 1975. Internet Archive.

Your write-up proved to be a great read, and I am grateful for the way you broke down complex concepts into comprehensible terms. Your writing style is clear and concise way of writing, and the provided a unique perspective on the topic. Especially, I enjoyed how you connected the topic to current events.

LikeLiked by 1 person