On October 26, 1967, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi (1919-80), who had ascended the Iranian throne 26 years earlier, crowned himself and his third wife and consort, Farah Diba (b. 1938), shahanshah (literally “king of kings” or “emperor” in Persian) and shahbanu (“lady of the shah“1 or empress) at Gulistan Palace in Tehran, where coronations of Qajar and Pahlavi kings were traditionally held.2

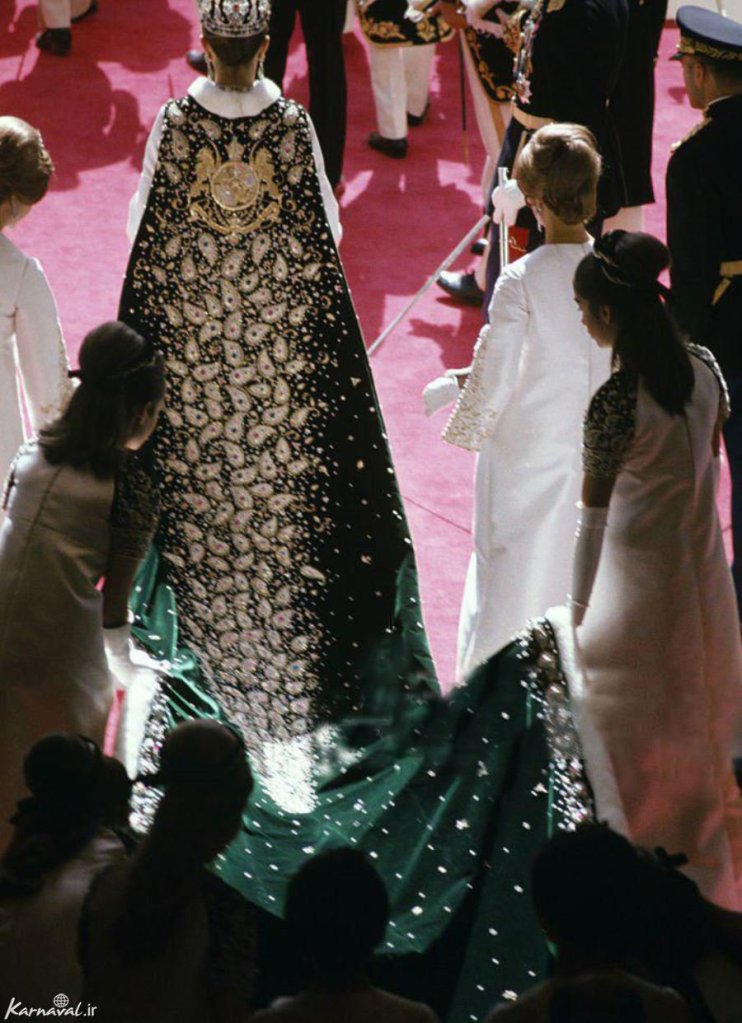

Figure 1.1. Marilyn Silverstone (American), The crowning of Farah Pahlavi, 1967, Marilyn Silverstone/Magnum Photos, source: Cambridge University Press.

The coronation of the last Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, took place after more than a quarter-century of his rule. Having ascended the throne as a weak king in 1941, after the Allies forced his father, Reza Shah Pahlavi (1878-1944), to abdicate and occupied Iran,3 Mohammad Reza Pahlavi had weathered various personal, political and economic storms and emerged victorious. In the years following the oil nationalization crisis of the early 1950s and the overthrow of Prime Minister Muhammad Mosaddeq (1880-1967) in 1953, the Shah had been able to consolidate his position,4 and the birth of a long-awaited son in 1960 seemed to virtually guarantee the stability and continuity of the monarchy. Both the Shah and his country were ready for a coronation.

The years preceding the 1967 coronation had seen a period of rapid modernization and socio-economic change, as well as improvement in the legal status of women, thanks to reforms brought about by the Shah’s White Revolution of 1963.5 His wife, Farah Diba, was a beneficiary of his modernization program, for she became the first consort in Iranian history to be crowned.6 Additionally, she would become regent in the event that the Shah died before the Crown Prince had turned 20, according to amendments made to the Constitution in the days leading up to the coronation.7 As the role of the Empress was now pivotal, although still subservient to that of her husband, who would place the crown on her head,8 she needed a new crown.

Notwithstanding the presence of the Nadiri throne, the Pahlavi crown and other regalia that had also been used for the coronation of previous Persian monarchs,9 many aspects of the 1967 ceremony were of European inspiration or origin. The blue horse-drawn coronation carriage, which took the Shah and Empress Farah from the Marble Palace to Gulistan Palace, was the handiwork of Joseph Kliemann (?-?), a Viennese coachmaker.10 Van Cleef and Arpels made Empress Farah’s crown, whose appearance and construction, unlike that of the Pahlavi crown, is decidedly European.11 Furthermore, the Empress, her entourage, her stepdaughter, Princess Shahnaz (b. 1940), and her sisters-in-law all wore French couture. It is worth pointing out that the Empress, who had no historical precedent to turn to and whose husband was eager to portray Iran as a major player in the Middle-Eastern geo-political arena that was on par with European monarchies, studied photographs and footage from the 1937 and 1953 British coronations.12 Emulating the 1953 example of Queen Elizabeth II (1926-2022), Empress Farah had six maids of honour for the purpose of holding aloft the train of her coronation robe.13

It is unclear how much Iran spent on the 1967 coronation. The coronation coach cost a stupendous $78,000;14 however, in an effort to reduce expenditure, Van Cleef and Arpels created the Empress’s crown and other jewels for the ceremony from loose stones stored in bowls inside a vault in Tehran’s Central Bank.15 During the week following the coronation, as a part of the festivities, foreign orchestras and companies performed at Rudaki Hall, a new concert venue; nonetheless, the musical performers’ fees and travel costs were paid for by the countries from which the orchestras originated.16 In terms of funding, the Central Council for the Imperial Celebrations (Shura-yi Markazi-yi Jashn-i Shahanshahi-yi Iran) alone contributed $3 million from its budget for the coronation.17

Empress Farah’s coronation ensemble

Coronation dress and robe

The ceremony took place on the Shah’s 48th birthday amid the magnificent interiors of the Reception Hall (tālār-i salām) of Gulistan Palace, newly renovated for the occasion.18 First, the six-year-old Crown Prince entered the hall and took his seat to the left of the Nadiri throne, followed by his mother,19 who was clad in a long, white satin Dior gown that had a 20-foot (six-metre) train.20 She sat to the right of the throne (figure 1.3), then came the Shah himself.21 After the Shah had crowned himself, the Empress, assisted by her ladies-in-waiting, presented herself to her husband,22 who sat enthroned (figure 1.2). Her attendants helped her put on a richly embellished emerald-green velvet robe, also a Dior design, with a square train measuring 26 feet and 3 inches (eight metres) in length.23 Then, the Shah placed the crown atop her bouffant coiffure (figure 1.1), in the manner of Emperor Napoleon I (1769-1821), who crowned Empress Joséphine (1763-1814), and the Russian tsars, who also bestowed the consort’s crown upon their wives, but in the process breaking away from Persian tradition.

Empress Farah’s plain white gown is reminiscent in its simplicity of the Colobium Sindonis, a linen-lawn garment that Queen Elizabeth II wore over her heavily embroidered coronation gown in 1953 for her investiture; she had then donned the Supertunica and Robe Royal, both made of cloth of gold, and received various items of regalia prior to her crowning with St. Edward’s Crown.24 By the time she departed Westminster Abbey, Queen Elizabeth was wearing a purple velvet, ermine-trimmed Robe of Estate more than 21 feet (6.5 metres) long over her coronation gown and had exchanged St. Edward’s Crown for the Imperial State Crown.25

The Empress of Iran was fascinated by the coronation of Queen Elizabeth, even staging a special screening of the event at Sa’dabad Palace while plans were underway for her own coronation,26 and there are echoes of the British ceremonial in the manner and the order in which the symbols of the Empress’s position—the luxurious coronation robe and the crown—are placed on her. Instead of a purple coronation robe with an ermine cape and border, Empress Farah wore one whose colour represented Islam (green); it was nonetheless trimmed with white mink.27 Marc Bohan (b. 1926), Dior’s head designer, created an outfit for her that was based on her specifications.28

The princess-line dress, which had a square neckline and long, “pagoda” sleeves, and the coronation robe were made in the workrooms of Pierre Krattinger (?-?), or “Monsieur Pierre,” a Swiss-born Iranian who was Dior’s representative in Tehran and was authorized to use the Dior label.29 Fourteen of Krattinger’s thirty dressmakers worked on the coronation garments of the Empress and her entourage (four ladies-in-waiting and six maids of honour).30 The ornate decoration on the Empress’s robe is the work of none other than Pouran Darroudi (?-?), a renowned Iranian embroiderer.31

The long, flowing coronation robe, which now resides at the Treasury of National Jewels in the Central Bank of Tehran, is open in the front. As figure 1.7 shows, the garment is sleeveless, with armholes extending down the robe so that it is open at the sides. Boteh or paisley motifs, a staple of the Persian decorative arts, embroidered with gold thread and beads mimicking the appearance of pearls, rubies and emeralds, run single file all around the edges of the robe and armholes (see figures 1.5 and 1.6). The emblem of Iran, which was actually the Pahlavi coat of arms, has also been picked out with gold thread;32 it sits above the cluster of paisley designs that cascades down the back of the robe (figures 1.8 and 1.9). The rest of the textile is dotted with bead-embroidered motifs of five-petal flowers and other floral, as well as foliate, patterns that are traditionally Persian. Darroudi used crystals from Austria, rather than precious stones, to save money and avoid adding weight to the velvet, which was produced by Bianchini in Paris.33 The mink fur came from Switzerland.34

The decision to entrust this vital commission to the House of Dior rather than any other French couturier was not taken arbitrarily. The women of the Pahlavi court, with the exception of Princess Shahnaz and Princess Ashraf (1919-2016), the Empress’s sister-in-law, both of whom frequently wore Jean Patou fashions, tended to favour Dior.35 Both Empress Farah and Queen Soraya (1932-2001), the Shah’s second wife, had worn Dior gowns for their 1950s weddings, and Farah had continued to wear Dior throughout the 1960s for important occasions, such as her 1962 state visit to the United States. She was therefore familiar with work of both Yves Saint Laurent (1936-2008), who had served as Dior’s head designer from 1958 to 1960, and Marc Bohan, Saint Laurent’s successor.

For Queen Elizabeth II, Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother (1900-2002) and Princess Margaret (1930-2002), British couturier Norman Hartnell (1901-79) was the go-to designer. Hartnell had made Queen Elizabeth’s wedding dress, as well as clothes for the bridal party, in 1948, and had performed the same task for Princess Margaret when she married in 1960. Moreover, he had also dressed the new sovereign, her maids of honour and various members of the British Royal family for the 1953 coronation. For Empress Farah, one of the takeaways from Elizabeth II’s coronation must have been the realization that hiring one designer to make the clothes for the participants and other prominent people at her own ceremony (i.e., her Pahlavi in-laws) would lend a unifying touch to their appearance. Thus, Bohan designed not only her coronation ensemble, but also the uniforms worn by her ten attendants and the dresses of her sisters-in-law, Princess Shams (1917-96) and Princess Fatemeh (1928-87).36

Crown and necklace

Empress Farah made history on October 26th, 1967 by becoming the first Iranian woman to be crowned, albeit as a consort. No crown had ever been created for an Iranian queen or empress prior to the one crafted by the prestigious jewellery firm of Van Cleef and Arpels, whose drawing for the Imperial consort’s crown was chosen out of fifty submissions in 1966.37 Iranian crown jewels were traditionally adorned with stones from the National Treasury, none of which could be taken out of the country.38 Over a period of six months, Pierre Arpels (1919-80) made twenty-four trips to Tehran to select the required gems from unset precious stones—which included thousands of emeralds and thousands of diamonds—located in the royal vault of Iran’s Central Bank, finally executing the order in a workshop he set up in the Treasury room.39 The result was a platinum crown set with 1,541 stones, consisting of 1,469 diamonds, 36 emeralds, 34 rubies, 2 spinels and 105 pearls (up to to 22 mm in length), and lined with an emerald-green velvet cap (figure 1.10).40 The crown, which has a 150-carat emerald at its centre, weighs 4.3 pounds.41

The crown takes the form of a circlet or band surmounted by swags and loops separating ornaments that gradually decrease in size so that the largest would rise above the centre of the wearer’s forehead, whereas the smallest would lie at the back of her head. Its design takes inspiration from European royal crowns and does not seem to incorporate any reference to Persian culture or history, whereas the Pahlavi crown, which was worn by the Shah, is replete with visual allusions to Iran’s Sasanian past.42

Van Cleef and Arpels also made a pair of earrings composed of emerald pendants and a necklace with an engraved hexagonal emerald fashioned as a pendant, four smaller emerald-cut emeralds, four pear-shaped pearls and eleven cushion-cut yellow diamonds and diamonds cut in antique-style (figure 1.11).43 Empress Farah can be seen wearing the earrings and necklace in figure 1.3. These, along with her crown, form part of the collection of the Treasury of National Jewels.

The dresses of the ladies-in-waiting and maids of honour

Typically, a group of unmarried young women of noble birth carried the ceremonial train of the queen regnant or queen consort during British coronations. In keeping with tradition, six train-bearers, known as maids of honour, attended on Queen Elizabeth (later The Queen Mother), consort of King George VI, and Queen Elizabeth II during the 1937 and 1953 coronations, respectively. Empress Farah similarly employed the services of six maids of honour, whose job description on the day of her own coronation entailed carrying her costume’s extremely long and heavy train. These aristocratic young ladies wore identical floor-length white satin gowns with empire waists and short sleeves of green velvet embroidered with paisley motifs that echoed the designs on the Empress’s own coronation robe (see figures 1.6, 1.8 and 1.12).44

The Empress drew a further parallel between herself and Queen Elizabeth II, posing with her maids of honour, three on either side of her (figure 1.12), in a style reminiscent of the newly crowned British monarch, surrounded by the six peers’ daughters who carried her robes, in Cecil Beaton’s (1904-80) iconic photograph (see figure 6.29 in Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom, 1953). The Empress of Iran’s maids of honour, like their British counterparts, wear long, white gloves and headdresses. The photograph in figure 1.12 seems to be a triumphant declaration that the Pahlavi dynasty, although its founder had ascended the Persian throne only about four decades earlier, now belonged to the same exclusive club as the House of Windsor.

The four ladies-in-waiting, who were senior to the maids of honour in the court hierarchy and accompanied the Empress as part of her procession of attendants, wore gowns of white French silk with hems reaching the floor and long, loose sleeves slit to the elbow.45 The outfits were unadorned, with the exception of the sleeves, whose cuffs and elbow-slits had a border of embroidered scrolling patterns studded with imitation emeralds and diamonds (figure 1.13).46