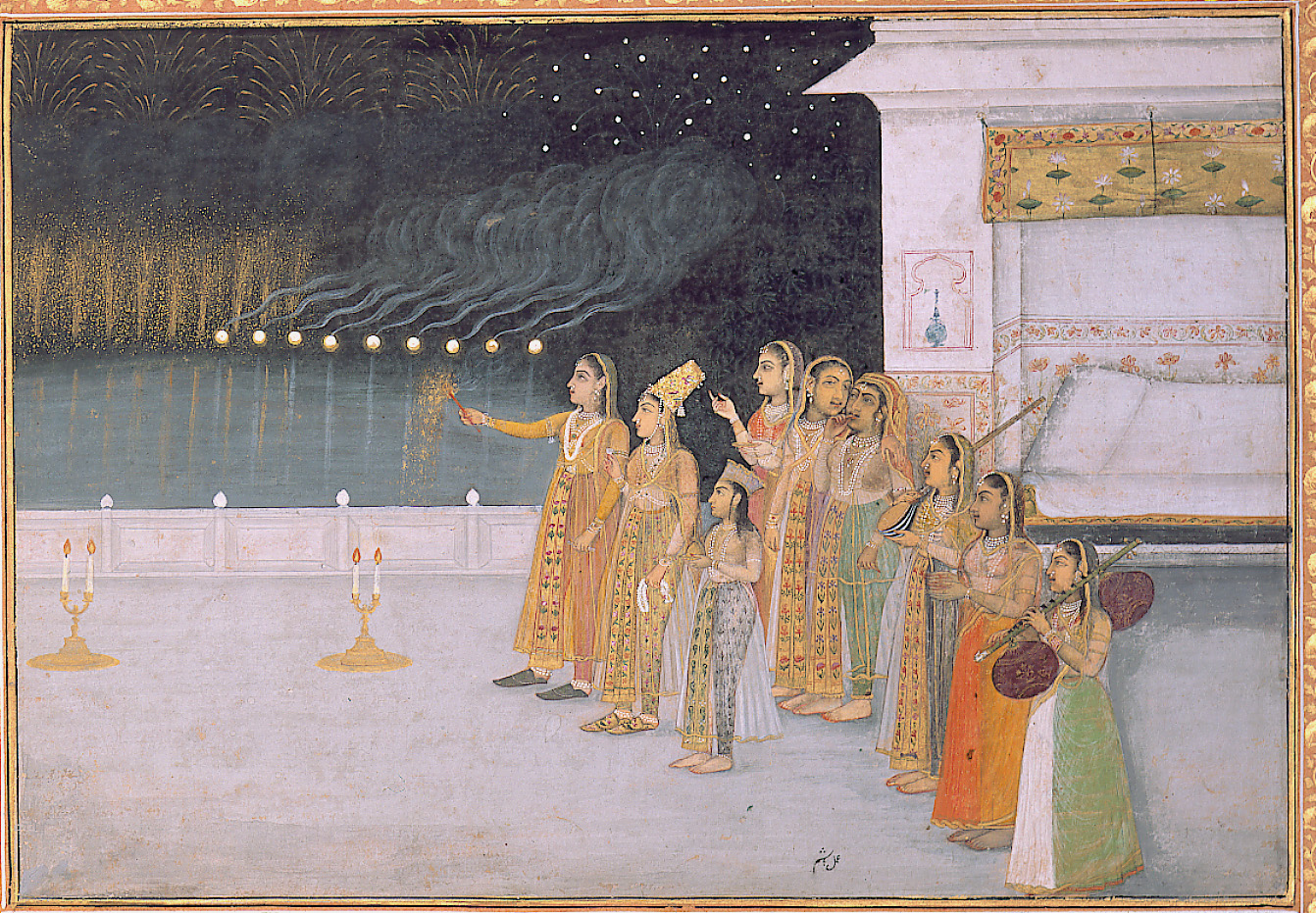

Figure 1.1. Attributed to Muhammad Faqirullah Khan (Indian), A Princess and Her Companions Enjoying a Terrace Ambiance, c. 1760-70, opaque watercolour and gold on paper, image: 11 x 7 1/2 in. (27.94 x 19.05 cm), Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, M.2005.159, source: LACMA.

Centuries before the Mughal empire (1526-1858) came into being, Indian cottons, particularly the sheer “Gangetic muslins” of Banaras and centres in Bengal, were famous in ancient Rome and Greece.1 Bernier, writing about his travels through the Mughal empire in 1670, mentions that karkhanas or court workshops employed weavers of muslin, which was used to make everything from turbans to girdles with golden flowers to women’s drawers.2 These last were so delicate that they could be worn out in the course of one night and the most expensive ones were beautifully embroidered.3 Additionally, in the seventeenth/early eighteenth centuries, many of Bengal’s best muslins were produced exclusively for the use of the Mughal court.4

The peshwaz, a long, front-opening gown of muslin or other sheer fabric worn over patterned trousers, was the court uniform of Muslim ladies from the pre-Mughal era onwards. In fact, women all over the Mughal empire wore this type of robe and it was also fashionable at northern Hindu courts. Women wore a shawl or large head-veil with the peshwaz.5

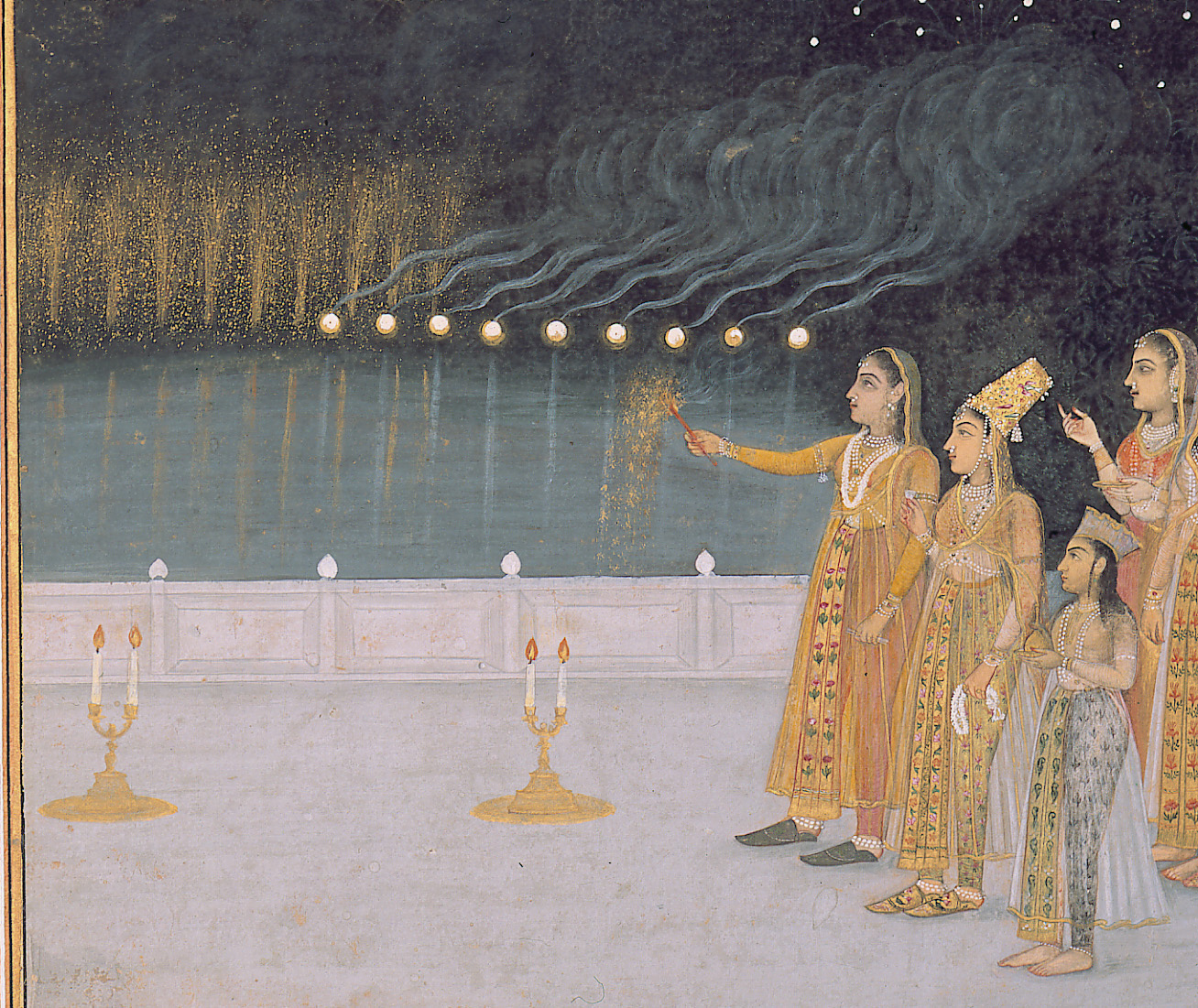

Miniature paintings from the early to mid-eighteenth century (see figures 1.2 and 1.4) show that women wore the peshwaz over a short bodice (choli) and tight-fitting trousers called churidar. The gowns of the Mughal princess, who wears a high Turkish cap and golden slippers as befits her status,6 and her companions split open in the front an inch or so under the bosom, the transparent muslin revealing their abdomens as well as the garments underneath, which in the princess’s case are richly embellished with floral motifs (figures 1.2 and 1.3). Each of the women in the centre and on the left in figure 1.4 wears her peshwaz tied around the neck and under the bosom, with the gaps between the two ends of the robe exposing the choli, midriff and churidar and also giving the legs freedom of movement. In both paintings, ribbon-like bands run down the length and along the hems of the skirts of the robes.

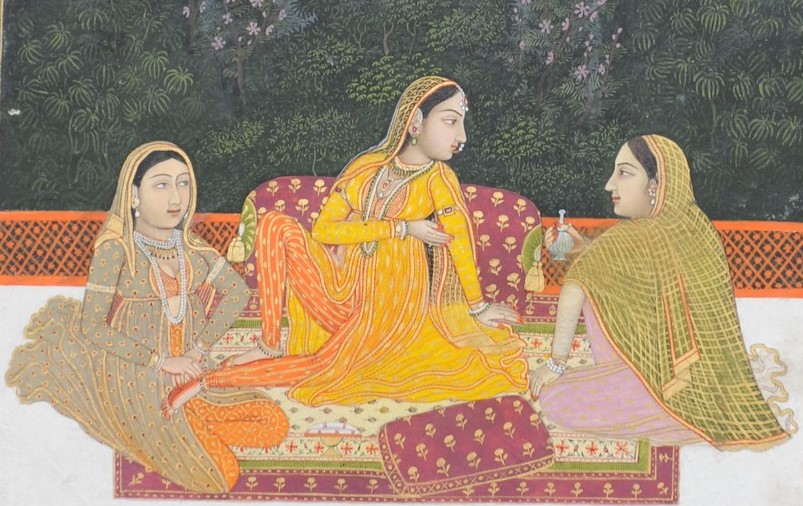

In contrast to the plain, vapour-thin robes of the ladies in figure 1.2, the women in figure 1.4 wear colourful gowns of thicker material embellished with patterns such as dots and the outfits in figure 1.5, a miniature work dating from about 1760 to 1770, also reflect a preference for less diaphanous, but more eye-catching over-garments. In this painting, a princess, who holds a flower aloft in one hand and the pipe of a hookah in the other, wears a peshwaz of a fine white fabric with pale-gold foliate motifs, through which the contours of her churidar and its yellow-and-red paisley designs are dimly visible. Her companions are similarly attired, but their robes appear to be of a more opaque material that possibly consists of layers of muslin; some wear brightly coloured gowns, which are decorated with teardrop-shaped motifs, like the blue peshwaz of the attendant who stands behind the princess holding a peacock fan and the hookah, or circles or crescents, as in the case of the ladies wearing yellow and red robes, respectively.

The peshwaz, which had been a calf-length garment in the first few decades of the eighteenth century (see figures 1.2 and 1.3), began to evolve by mid-century into a less gossamer-like robe with a wide, billowing, floor-length skirt (figure 1.5), a trend that would continue into the 1800s (figure 1.6). Unlike the depictions of the peshwaz in figure 1.4, however, the circa 1760s and 1800 versions of the robe, as worn by the ladies in figures 1.5 and 1.6, respectively, fasten at the neck and between the breasts so that almost nothing of the underlying choli is visible through the resulting slit in the gown’s bodice.

1770s–90s

Peshwaz, late 18th century to early 19th century

The Victoria and Albert Museum in London has in its collection a rare example of a peshwaz belonging to the late eighteenth to early nineteenth centuries (see figures 1.7 to 1.9), that is, the same approximate time period as the robes depicted in figures 1.5 and 1.6. Made in northern India, this peshwaz is of fine white muslin decorated with bands of silver-gilt embroidered with floral motifs in red foil and sequins and edged with green foil; these run along the neck, front opening of the bodice, waist seam, armholes and sleeve cuffs, as well as the edges and hems of the skirt panels. Silver-gilt strip couched into a motif of four-petal blossoms and dots, divided by rows and columns of serrated silver-gilt foil, further embellishes the fabric of the sleeves and skirt.7

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, wood-blocks primed with paste were frequently used to outline embroidery designs,8 and indeed, the empty circles and outlines of the four-petal flowers on one of the sleeves (see figure 1.7) of this particular garment seem to be evidence that these designs were first block-printed onto the fabric. The flowering-plant motif dominated Mughal arts and crafts from the mid-seventeenth century onwards,9 and it appears here in a stylized form in the embroidered blossoms, stems and leaves that compose the bands of decorative trim, although decoration tended to be absent from the muslins used to make the peshwaz in the first half of the eighteenth century.

As figures 1.7 and 1.8 show, the full, floor-length skirt is tucked into the waist seam by means of innumerable gathers, which fall in folds down the length of the gown, a structural feature that also characterizes the robes seen in figure 1.6.

Figure 1.9, a black-and-white photograph of the high-waisted gown with its bodice unfastened, offers further insight into the construction of the peshwaz of the late 1700s to early 1800s. The bodice opens at centre front from the neck down to the top of the skirt, creating a large, rectangle-shaped aperture that would have allowed the wearer to comfortably pull the gown over her head. There is no corresponding gap in the skirt, but rather a length-wise split that extends from the bottom of one of the decorative bands that border the bodice’s front opening all the way down to the hem. This dressmaking technique accomplishes two things. Firstly, it causes the slit in the skirt to move to centre front when the open edges of the bodice are brought together: as a result, the silver-gilt bands edging the skirt opening overlap each other, concealing the wearer’s abdomen even if the skirt were to flap open (see figures 1.7 and 1.8). Secondly, it gives the skirt extra fabric, which curves out from the waist to create a bell-shaped silhouette when the gap in the bodice is closed.

The photographs in figures 1.7 and 1.8 are nonetheless somewhat misleading, for the gown would not have closed completely over the wearer’s bosom; there would in fact have been a vertical slit in the bodice between the neck and the waist, in keeping with the prevailing fashion.

Notes

1. Veronica Murphy, “Textiles,” in The Indian Heritage: Court life and Arts under Mughal Rule, ed. Robert Skelton (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1982), 78, Internet Archive.

2. François Bernier, Travels in the Mogul Empire: A.D. 1656-1668, trans. Archibald Constable, 2nd ed. (London: Humphrey Milford, Oxford University Press, 1914), 258-59, Google Books.

3. Ibid., 259.

4. Murphy, “Textiles,” 80.

5. “Peshwaz | V&A Explore The Collections,” Victoria and Albert Museum, accessed March 7, 2023, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O470782/peshwaz/.

6. “San Diego Museum of Art – Ladies of the Imperial Harem Celebrating the Night of Shab-i Barat,” San Diego Museum of Art, accessed March 8, 2023, https://collection.sdmart.org/objects-1/info/5099.

7. “Peshwaz | V&A Explore The Collections.”

8. John Irwin, “Textiles,” in The Art of India and Pakistan: A Commemorative Catalogue of the Exhibition Held at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1947-8, ed. Sir Leigh Ashton (London: Faber and Faber, 1950), 201.

9. Murphy, “Textiles,” 78.

Bibliography

Bernier, François. Travels in the Mogul Empire: A.D. 1656-1668. Translated by Archibald Constable. 2nd ed. London: Humphrey Milford, Oxford University Press, 1914. Google Books.

Irwin, John. “Textiles.” In The Art of India and Pakistan: A Commemorative Catalogue of the Exhibition Held at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1947-8, edited by Sir Leigh Ashton, 201-10. London: Faber and Faber, 1950. Internet Archive.

Murphy, Veronica. “Textiles.” In The Indian Heritage: Court life and Arts under Mughal Rule, edited by Robert Skelton, 78-81. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1982. Internet Archive.

San Diego Museum of Art. “San Diego Museum of Art – Ladies of the Imperial Harem Celebrating the Night of Shab-i Barat.” Accessed March 8, 2023. https://collection.sdmart.org/objects-1/info/5099.

Victoria and Albert Museum. “Peshwaz | V&A Explore The Collections.” Accessed March 7, 2023. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O470782/peshwaz/.